A Classroom on the Water

Tonia Lovejoy’s sailing expedition to be shared with students

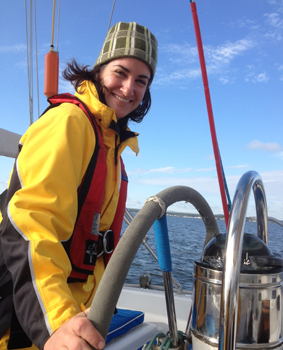

TONIA LOVEJOY'S eyes shift to the right as she sails to faraway places. We’re sitting at a table in a coffee shop, but her mind travels the globe – because she has been there. She’s a citizen of a beautiful nation, says Lovejoy, reciting the quote that inspires her company name.

“I am a citizen of the most beautiful nation on earth. A nation whose laws are harsh yet simple, a nation that never cheats, which is immense and without borders, where life is lived in the present. In this limitless nation, this nation of wind, light, and peace, there is no other ruler besides the sea.” -Bernard Moitessier, French yachtsman and author

Lovejoy, founder of BEAUTIFUL NATION and WILMINGTON NATIVE, sets sail this fall on her group’s first expedition and an all-female team. Using multimedia and online discussions, Beautiful Nation intends to connect with students during the voyage, with explorers talking with participating classrooms through video calls and sharing data on water quality through apps.

Her dream is that all children will be globally aware. She uses terms like “geographically literate,” “global mentors,” and “global community.”

From their ship, Makulu, Lovejoy and her colleagues have set up a floating classroom to teach global skills to children in classrooms via video conferencing. It’s more like a floating school, since they plan to invite experts to teach on a variety of subject matter. One expert, Bonnie Monteleone from University of North Carolina Wilmington, will teach a science and ecology lesson about garbage patches in all the earth’s oceans.

The crew will sail aboard the ship to six continents, thirty countries, with forty-five planned port stops over 760 expedition days – all while being followed online by more than 1.6 million students.

Lovejoy says they want students to be “solutionary” in answering the question: How does where we live affect how we live?

“My goal is that students will conjure up the mental map of the world and visualize a part of the world, the season, how the people feel based on geography, do they have water, do they have what they need? This can be the key to business success whether they are artists or business owners,” she says.

Her connection to Wilmington means Lovejoy will be able to visit the classrooms that followed her.

Lovejoy became captain of the ship by a meandering route, but sailing was in her blood.

“My dad was in the Navy. His dad was in the Navy. And my mom’s dad was in the Navy,” Lovejoy says.

Her parents grew up in the area, met in ninth grade, and Wilmington was always home base during her dad’s Navy career. It was the place they came to visit family and the place where they retired when the career ran its course.

“My parents built a boat and we lived on it for the first few years of my life. We sailed it to wherever my dad was stationed,” Lovejoy says. “I really resented sailing because it was what my parents did that took me away from my friends. My mom is an artist. She gave me projects to do, and I wanted to major in art. Mom said ‘Only if you pair it with business.’”

Lovejoy majored in English literature at the College of Charleston and upon graduation in 2000, got a job with a publisher writing back cover blurbs and editing bios.

After 9/11, Lovejoy felt isolated from the global community, and with travel in her blood, she wanted to do something. She joined the Peace Corps and went to Nepal. The experience helped her reflect on her own community, compared to where she was, Lovejoy says.

Happy in Nepal and speaking the language fluently, she thought she would stay there. Her time ended abruptly when they were evacuated due to civil war. But that experience became her foundation for becoming a global educator.

Back in Wilmington, she worked for Insider’s Guide and taught English to migrant workers through Cape Fear Community College. Her friend applied for a job writing children’s stories while sailing around the world, but didn’t get it. She told Lovejoy, “You have to apply for this job; it was made for you.”

A week later she was in New York City, and two weeks later on board Makulu sailing from Australia to New York over a twenty-eight month period, Lovejoy says. Working with the Reach the World program, Lovejoy wrote to Title I elementary schools in New York to meet their social studies curriculum needs.

Lovejoy knew the rules for peace, safety, and survival, she says. On board with four other people and no television or telephone, she learned more about how to get along with people.

“That experience convinced me that I was a sailor. All those years of spending time on my parent’s boat came back to me,” she says.

Another reality became apparent to Lovejoy. She saw no female captains, no captains of color. She was in New York teaching literacy when an opportunity came along. Atlantic Yachting in New York said they’d pay for her captain’s license if she would work for them for a summer. Having a captain’s license opened new avenues.

Reach the World’s focus evolved, so Lovejoy moved on to working with international students to create material for classrooms. She and another woman did all the training, editing, setting up, and facilitating of more than 500 video calls with classrooms from 105 countries.

“Through that work I came to teaching globally,” she says.

In 2008 with a captain’s license in hand, Lovejoy and the women from the Makulu initiated a plan to sail and teach again. They wanted instruction to be free to classrooms, and they wanted to use video to portray the effects that they see.

In 2010, Lovejoy received the The Catalyst Initiative, a grant awarded by Hewlett Packard (HP) to nonprofits that were using technology in innovative ways to teach. Beautiful Nation won one of their first grants. HP brought all the grant winners together to share best practices and paid for the fellows to visit each other.

From exposure to best practices with HP fellows, a format was born. Beautiful Nation’s geosocial network (beautifulnationproject.org) offers several different topics, called channels. One of them is sponsored by the History Channel, which presented a $10,000 grant. Others such as energy, marine debris, water quality, transportation, and food provide information based on literacy and grade level. Companies are able to sponsor channels that meet their interests. The crew has put in over 300,000 hours of work to build the $100,000 website.

Still adhering to the Peace Corps motto, think globally, act locally, Lovejoy knows what the success of her program will look like.

“The class will do a local project,” she says, “take some action.”

Lovejoy will present an overview of the program at the New Hanover County Northeast Library on August 26 at 6 p.m. Weather permitting, she will be in the Wilmington area November 2-5 working with local schools and community agencies.